“What a child can do today with assistance, she will be able to do tomorrow by herself.” – Lev Vygotsky

With every major skill that we learn, there are often supports in place to protect us from harm as we learn them. Training wheels help to build muscle memory, so when they’re removed, the rider’s “training” kicks in, and they can stay balanced on their own. Those who aren’t strong swimmers can use floaties to keep their heads above water while they build their swimming muscles. New drivers often learn to drive with a trained passenger who has their own brakes and wheel control.

These supports are in place to protect the learner, but they also teach them the necessary skills to become independent. This is scaffolding. As an educator, you can put the training wheels on, so to speak, so that learners don’t get frustrated with the learning process and give up. When they’re ready, you take the wheels off and give them the freedom to demonstrate their skills.

This freedom often comes in stages. That’s what we’re here to talk about: What does scaffolding look like in instruction, how can one use it in their classroom, and why is it an essential part of the learning process? Keep reading for a high-level overview of scaffolding that can help you reach the individual learners in your classroom.

What is scaffolding in teaching?

Scaffolding is a teaching technique in which the instructor provides and gradually removes supports for the student as they become more confident, enabling them to achieve mastery.

So, what is a “support?” And how does the instructor know when to remove them?

Support can take many forms, including physical materials such as graphic organizers or a teaching practice like individualization. Anything that is strategically provided to help students inch forward, especially if it’s catered to their specific learning needs, is a form of support.

Many instructional models use scaffolding, including Response to Intervention (RTI) and Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS).

There are several types of scaffolding, such as:

- Conceptual - guiding a student to understand a certain concept

- Instructional - breaking down learning tasks into more manageable steps or bites in order to build in complexity

- Social - enables students to learn through social structures and interaction, such as group work and collaborative learning

- Resource - gives students specific resources to support their learning, such as graphic organizers

- Procedural - supports that help students follow procedures or use strategies, such as rubrics or outlines

- Metacognitive - develops a student’s understanding of their own thought processes and learning strategies

- Emotional - supports the student’s emotional needs through encouragement and feedback

- Linguistic - Enables language development

An instructor will know when to remove levels of support when the student passes certain checkpoints in their progress. The teacher can assess this progress through formative assessments, e.g. quizzes, homework, check-ins, bellringers, exit tickets. For some, the student achieving certain levels of Mastery in the unit’s standards may be the signal to start removing support and encouraging autonomy. The teacher may also feel that the student is ready to move on without supports if the student starts to take the initiative, is more confident, or is moving through their existing tasks with ease.

What is the research behind scaffolding, and who came up with it?

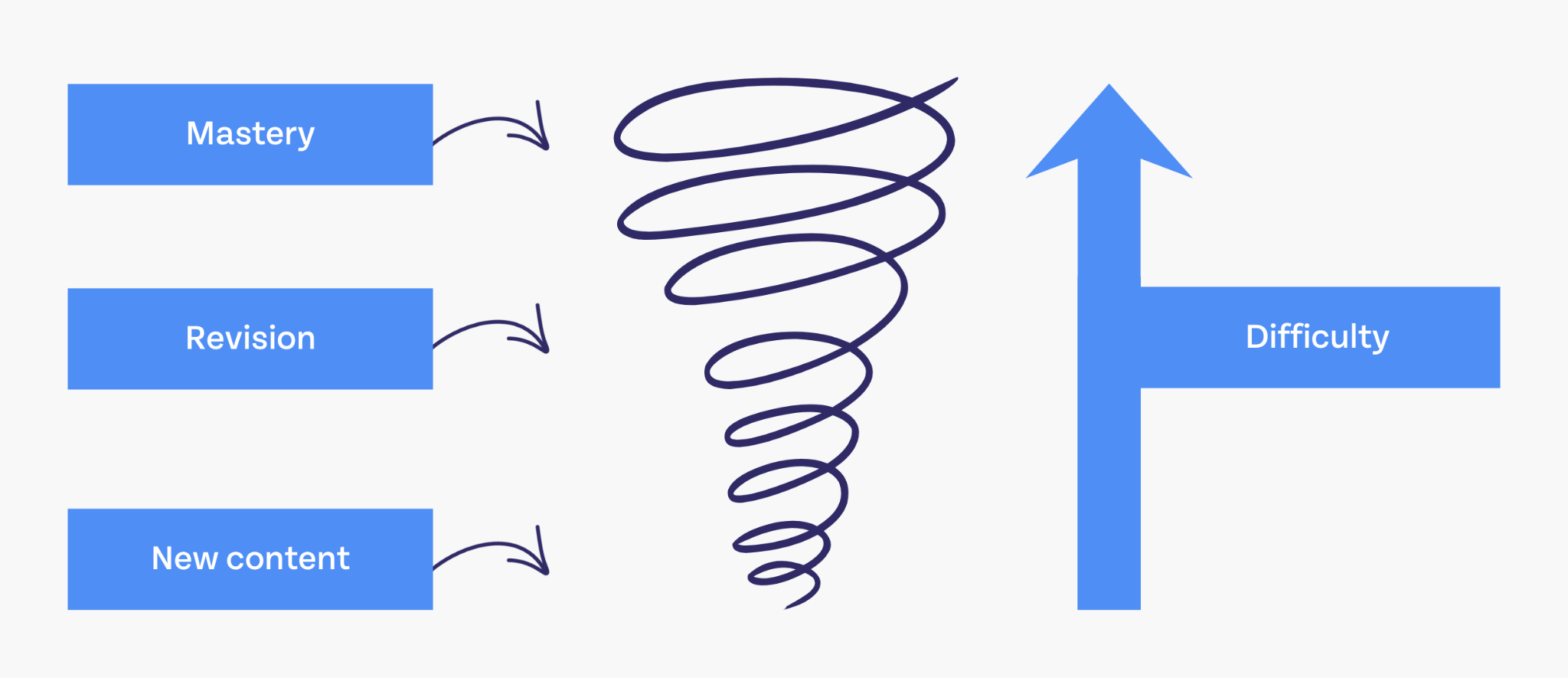

In the 1950s, psychologist Jerome Bruner introduced the concept of scaffolding through the context of language acquisition in children. His research focused on how children acquire language, saying that learning is an active process in which the learner internalizes new skills and knowledge, slowly increasing in levels of “complexity and abstraction” while also revisiting basic concepts (Simply Psychology).

In other words, children need to be actively involved in their learning to deeply understand. They can reach those expert levels of understanding that are required for complex and abstract concepts, while using the things they already know to build their knowledge.

Rather than visualizing progress as a ladder or a line extending in one direction, Bruner describes this journey as a spiral.

The learning process is facilitated by an expert who guides the student through self-directed, active learning, focusing on a goal that is slightly out of their comfort zone, then gradually removing support as they gain confidence and skill.

Our current understanding of scaffolding, however, could not exist without Lev Vygotsky, who developed the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development nearly 30 years earlier.

In Vygotsky’s theories, a child’s level of development plays a crucial role in their ability to learn certain concepts; therefore, measuring all children by the same measuring stick when they’re at different levels of development would produce an inaccurate measure of that student’s capabilities.

For example, it wouldn’t make sense to teach kindergarten students the conventions of grammar beyond basic sentence structure. They are not developmentally prepared for content of that complexity. However, in every classroom, at every grade level, there will be students who are taught the same content while they are at different levels of development. They will acquire knowledge differently.

According to Vygotsky’s theory, no two students learn in the same way, so their teaching should be adapted to their level of development, their willingness to learn, and several other factors.

This type of individualized teaching can be guided by the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD).

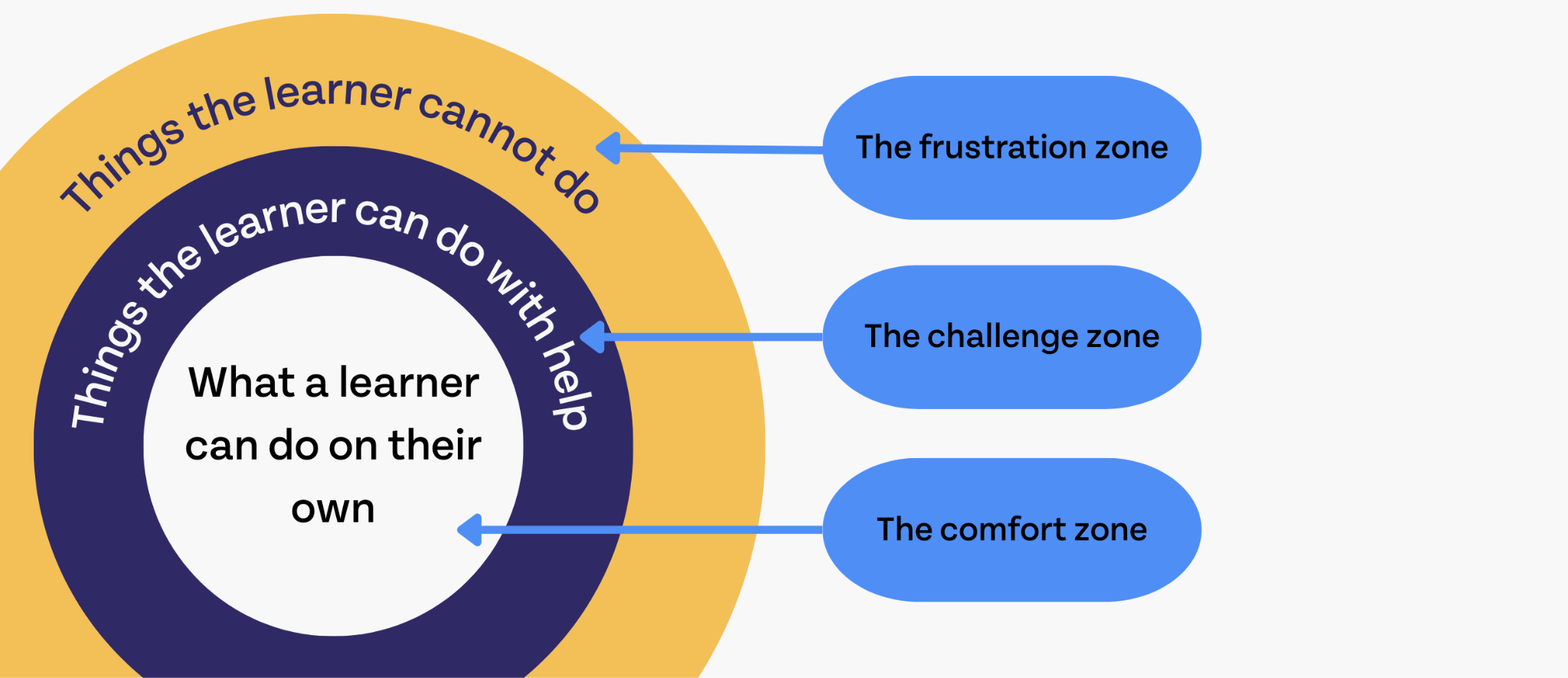

What is the Zone of Proximal Development?

The Zone of Proximal Development is the area in which a child is most likely to learn or gain new skills. This zone is just outside their comfort zone, but not far enough away from what they know to cause stress or frustration.

According to Vygotsky, a child is capable of doing more with the help of others than they can do on their own. If you’re a teacher, then you may already be drawing some connections in your everyday practices.

Do you split students off into groups early on in a unit?

Do you pair them with partners when they’re a little bit more confident than they were at the beginning?

Once they’re more confident, do you give them projects that they have to accomplish on their own?

If so, then you’re using the Zone of Proximal Development to guide the structure of your lessons.

When you offer support to students to help them extend their knowledge (such as putting them in groups), you’re using scaffolding to help students gain new knowledge and skills.

Current research still supports scaffolding as best practice

In one study, students learning English were split into two groups–one that would receive scaffolding support and one that would not.

Students who were taught with scaffolding had significantly higher reading comprehension and better critical thinking skills than their peers. Perhaps most importantly, they found that students who received scaffolding support showed a high level of autonomy after the study was over.

The authors have this to say about the effects of scaffolding on learning:

“To be truly meaningful, instruction should be focused on trying to be the bridge between students’ actual ZPD and the expected performance in a higher ZPD. Assistance and guidance provided to students can facilitate their transition from one ZPD to another in a hierarchal level in a relaxed, safe and enjoyable way…At the curricular level, making language instruction more meaningful implies weaving in particular content that can be connected to the students’ lived experiences so that their learning can become situated rather than abstract, collaborative and guided until autonomy is achieved.”

There are a few important takeaways here:

- The “zone of proximal development” isn’t just informed by the student’s ability to grow and extend into the next level of learning; it’s also informed by the higher expectations of performance goals and signposts.

- Students should feel comfortable and secure as they transition into deeper levels of learning. If students feel unsafe or are not enjoying that transition, then their zone of proximal development may be lower than previously thought.

- Instruction should be meaningful beyond the simple “goal-directed” learning process. Connecting student learning to their real lives anchors them to their learning.

- The student being self-assured and confident in their learning is a prerequisite to autonomy.

How to Scaffold

There are many existing studies on scaffolding that go into great detail about which methods of scaffolding are most effective. We will condense some of those here, so you don’t have to deep dive into academic literature to take something into your practice today.

First, let’s talk about some common scaffolding techniques that have been tried and tested.

Scripting

Per the study: “Effects of regulated learning scaffolding on regulation strategies and academic performance: A meta-analysis,” scripting is an extremely effective scaffold for cognitive strategies (strategies that promote metacognition and teach strategies for learning).

Scripting models the kind of behaviors that enable positive learning outcomes. They “enable students to anchor newly acquired knowledge within prior knowledge…stimulate the activation of learning strategies, and enhance deeper processing of information…” (Section 5.2.2).

The authors list several kinds of scripts:

- A teacher’s oral presentation

- Role assignment

- Question prompts

- Peer feedback

- Worked examples

- Social

- Content-oriented

- Communication-oriented, collaborative

- Metacognition

If you’ve ever given a student “sentence stems,” then you’ve given them a script! Here are some other examples of scripts that you might be more familiar with:

- Reflection questions that ask students to use a specific format to reflect on their learning progress or strategies, e.g. “I used _____ strategy to solve this problem”

- Emotional charts that help students define and verbalize their emotional state

- Actual scripts for groups to follow while they problem solve or work through a task

- Call and response during instruction, so students are forced to identify when a common step is called for or when a mistake is about to be made

You can write scripts for just about anything! As the student is forced to work through a problem in a new way, they evaluate their existing strategies, incorporate new knowledge, and practice new skills. What do you want your students to try that might help them learn better? Try writing a script that walks them through this new process step-by-step. Make it fun and interesting (such as using characters they love or song lyrics they’re familiar with) so they’ll enjoy trying new things.

Modeling

Modeling is when the teacher (or instructional partner) models a strategy or problem-solving method by walking through the steps, verbalizing their thoughts aloud, and acknowledging when failures happen. Modeling both failures and successes can help students avoid missteps, learn new techniques, and even consider their own strategies to improve their processes.

When teaching students a brand-new skill, it’s a great idea to modelthe strategy or method you’re hoping to teach. “I do, we do, you do,” is a common expression that follows a great catch-and-release method for modeling. First, the teacher models the task; then, the teacher does it with the class’s input; and finally, the student does it on their own.

Here are some examples of modeling:

- Solving several math problems on the board before solving similar problems with the class’ input

- Editing and reorganizing an essay you’ve written with the students before students edit their own writing

- Tracing print or cursive letters on the board so students can see how you’re holding the pen, moving your hand, or which direction you’re going

- Reading through a passage aloud and writing down thoughts you have as you read to model analysis methods and deep thinking strategies, e.g., “This makes me wonder…” “This seems important because…” “This doesn’t make sense to me…”

- Walking through the steps of a lab, modeling proper behaviors such as donning goggles, wearing gloves, and/or using safety equipment

Chunking

Chunking is when the teacher breaks down large, complex, or difficult tasks into smaller, more manageable chunks. If you like to sort your dishes before washing them or organize your groceries before checking out at the register, then you’re a chunker. You recognize that proper preparation ahead of time can make the following tasks easier and more successful.

Here are some examples of chunking:

- Breaking down an essay assignment into several steps, such as brainstorming, outlining, drafting, editing, and revising

- Assigning sections of a required reading, rather than assigning the entire reading at once

- Breaking down a complex problem into smaller steps, using common strategies or formulas

- Asking students to go through a test and complete easier questions before moving on to more difficult ones

Using resources

Physical resources are a common and essential form of scaffolding. Students may or may not have these as part of the individual learning plans (IEPs). If it were up to Vygotsky, every student would likely have access to these resources in the beginning stages of the learning process.

Here are some common examples of resources that are often used as scaffolds:

- Graphic organizers

- Visual reminders, e.g., charts, rules and procedures, definitions of words

- Rubrics

- Sentence starters and prompts

- Vocabulary lists

- Dictionaries, thesauruses, and/or English to native language dictionaries

Designing your own scaffolds

Next, we can discuss designing your own scaffolds, which are tailored to your specific lessons, students, and goals.

In “A Framework for Designing Scaffolds that Improve Motivation and Engagement,” the authors list several crucial ingredients for a well-designed scaffold, including:

- Choosing a task that the student considers worth doing. The perceived “value” of a task can motivate a student to stay engaged with it.

- Anchoring the task to Mastery goals. Without Mastery-oriented goals, students may compare their performance to that of others or hesitate to engage with challenging tasks.

- Promoting belonging. Students feel more engaged with tasks, more motivated, and experience greater enjoyment when they feel a sense of connection and belonging.

- Expecting success. Students themselves should feel confident that they will succeed. They should feel in control of their success and not like victims of bad circumstances. This requires fostering self-efficacy in students.

- Modeling appropriate responses to academic failure and success. The student’s positive and negative reactions to academic progress directly relate to their motivation to learn.

- Enabling autonomy. A student’s motivation becomes more intrinsic when they have autonomy. Autonomy is associated with greater engagement and academic achievement.

Scaffolding can take the form of physical materials or the design of instruction itself. The study includes a table that provides numerous examples of these types of scaffolds, especially as they relate to project-based learning.

If you know your students well, through interacting with them, seeing their assessment scores, and listening to their thinking processes, then it’s likely you’ve thought to yourself, “I wonder if this would help them understand?”

One incredible special education teacher (also the author’s father) described this experience exactly. With one of his non-verbal students, he found that food-related instruction kept them interested and helped them build a larger vocabulary with their assistive speaking device. So, when teaching this student something new, he’d build specific resources and write food-related examples to help them succeed.

This is, perhaps, an extraordinary level of support that many classroom teachers don’t have the time for. However, for many students, a simple check-in and reteach would go a long way, and this is a fast and effective support that can be provided at any time.

Tools that can help you Scaffold

At Eduphoria, it’s our mission to “simplify the aha.” The “aha” moments are those moments of learning that teachers provide for their students when they finally break through to them. However, teachers can also have “aha” moments, and our tools are meant to facilitate them.

First, our assessment software and data management system: Aware.

To provide students with appropriate support, teachers need data. Aware is where you can build, administer, and analyze your assessment scores.

We offer data visualization that makes it fast and easy to make actionable insights about each student in your classroom.

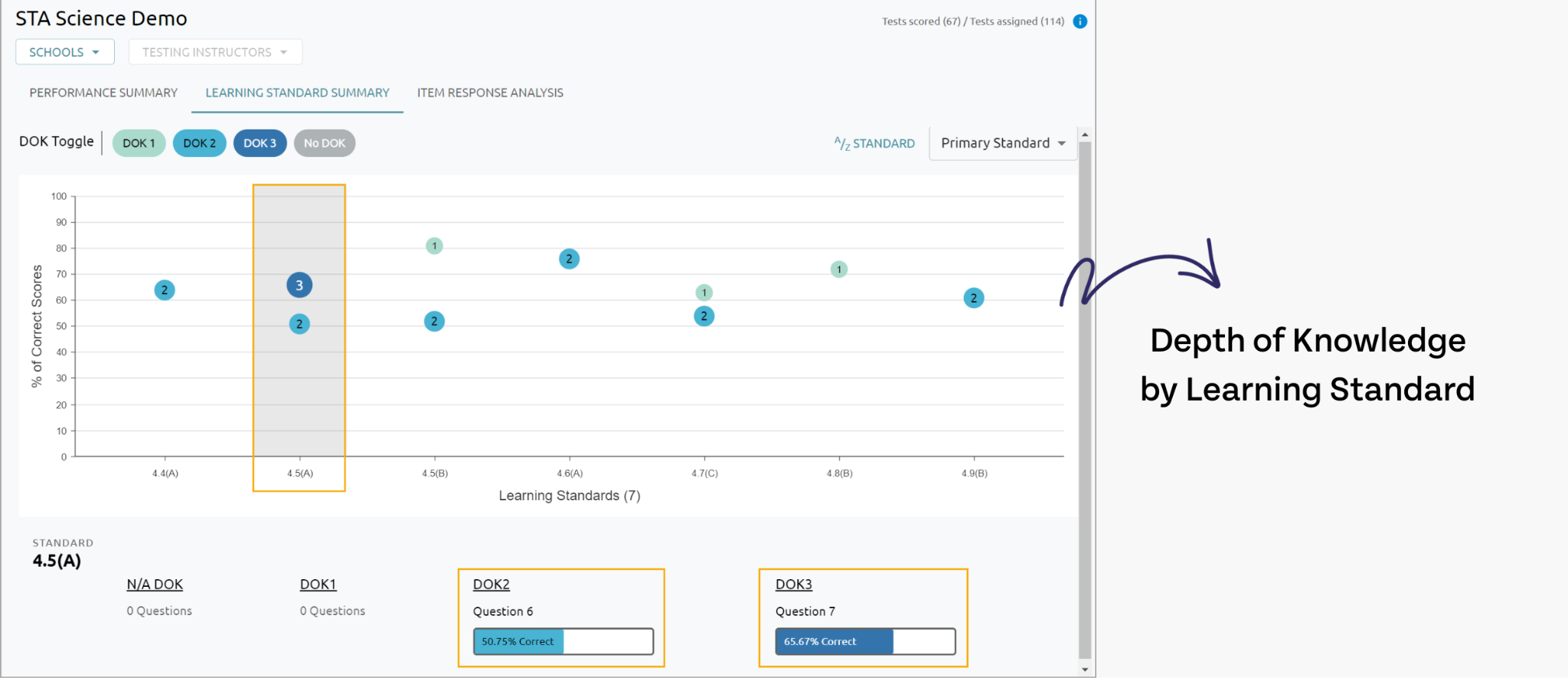

Single-Test Analysis (STA) is our most popular data visualization tool with teachers. With STA, you can see not just the individual assessment scores in your classroom but also which questions and learning standards were trickiest.

If you’re looking for data that can help you form groups, you can filter the information in several helpful ways.

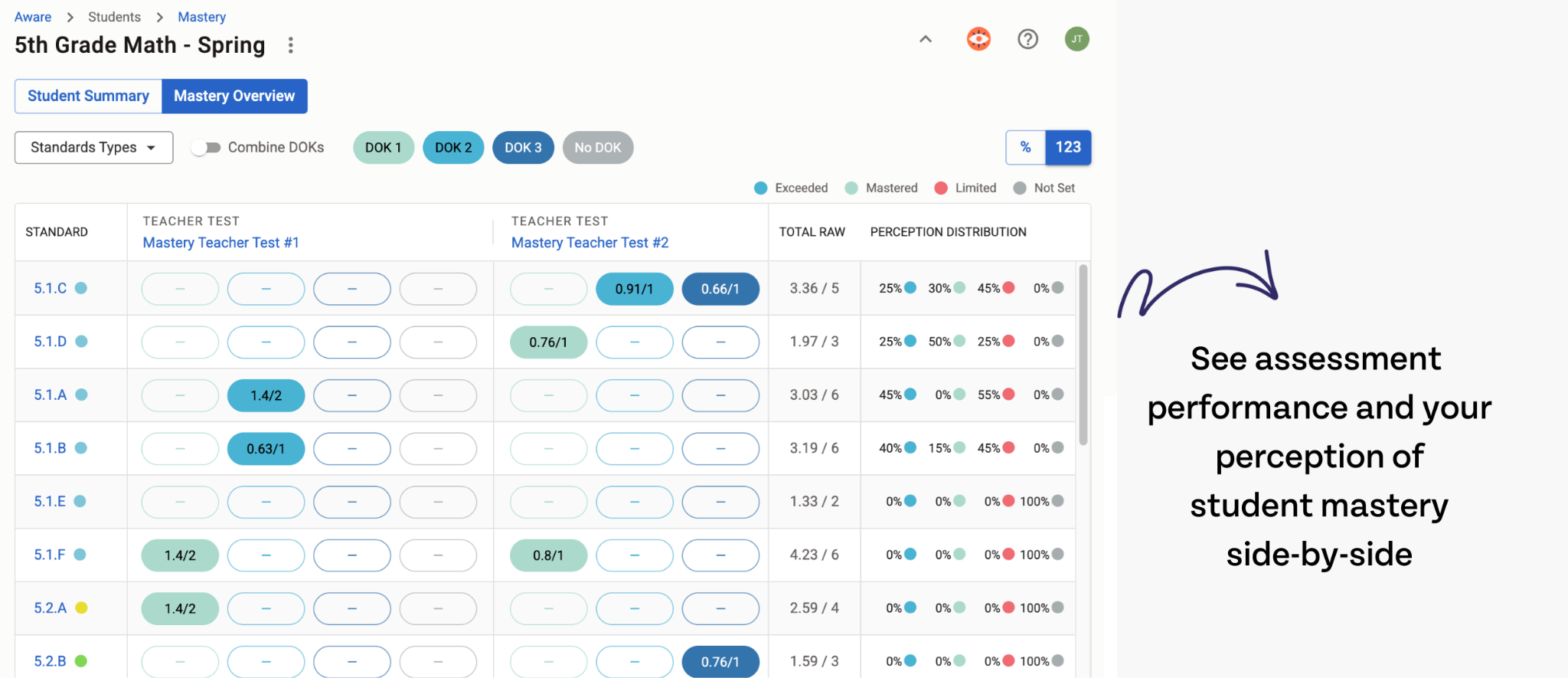

Once you have the data, you can group students according to their learning needs and add them to Mastery Tracker.

Mastery Tracker is our tool for student monitoring and individualization. Once you know which standards your students are struggling to master, you can document your interventions and conversations with them in the tracker, updating their Mastery Level as you spend more time in intervention. While their assessment scores automatically place them at a certain level of Mastery, the teacher is always the expert on that student’s understanding and can update it at any time.

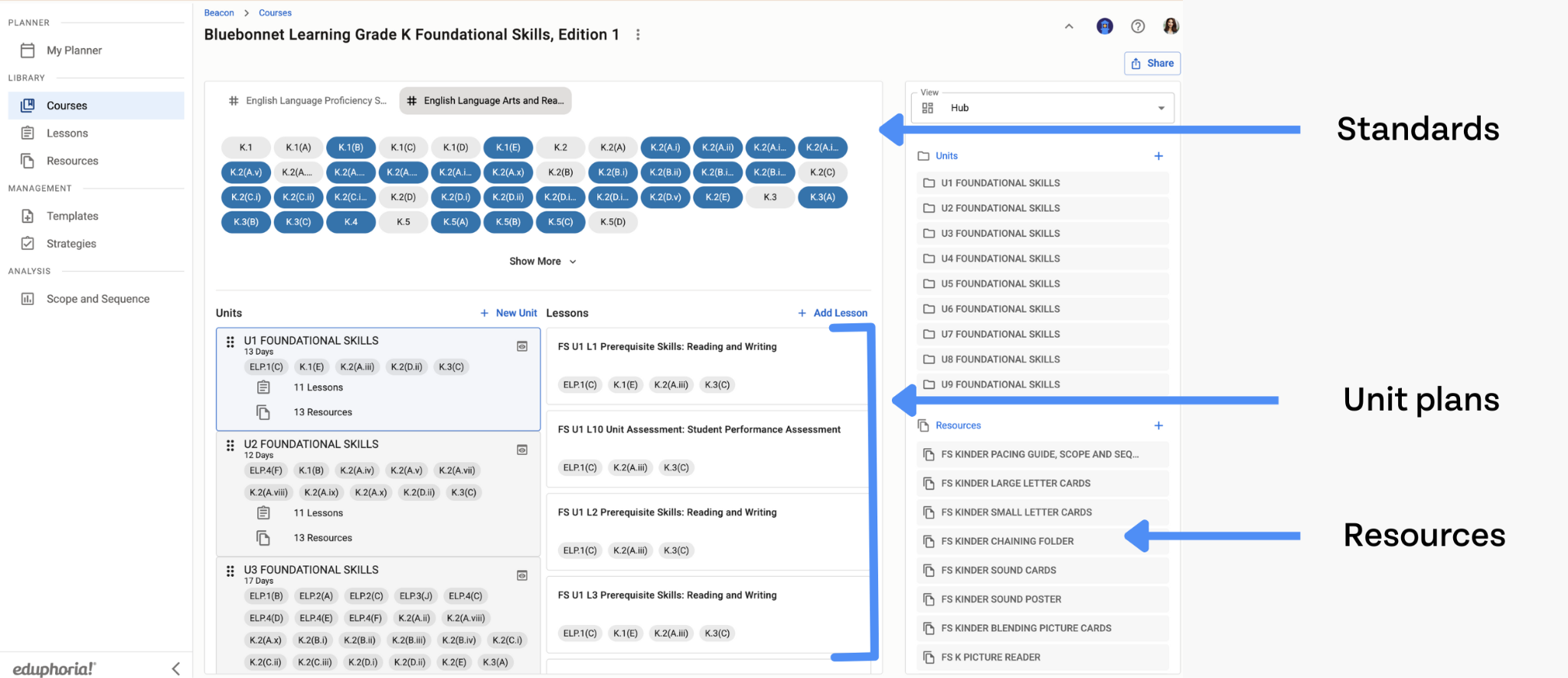

Finally, once you have the data you need to make decisions about your students, you can head to Beacon, our curriculum management and lesson planning tool.

Strategizing for individual students is easier with Beacon

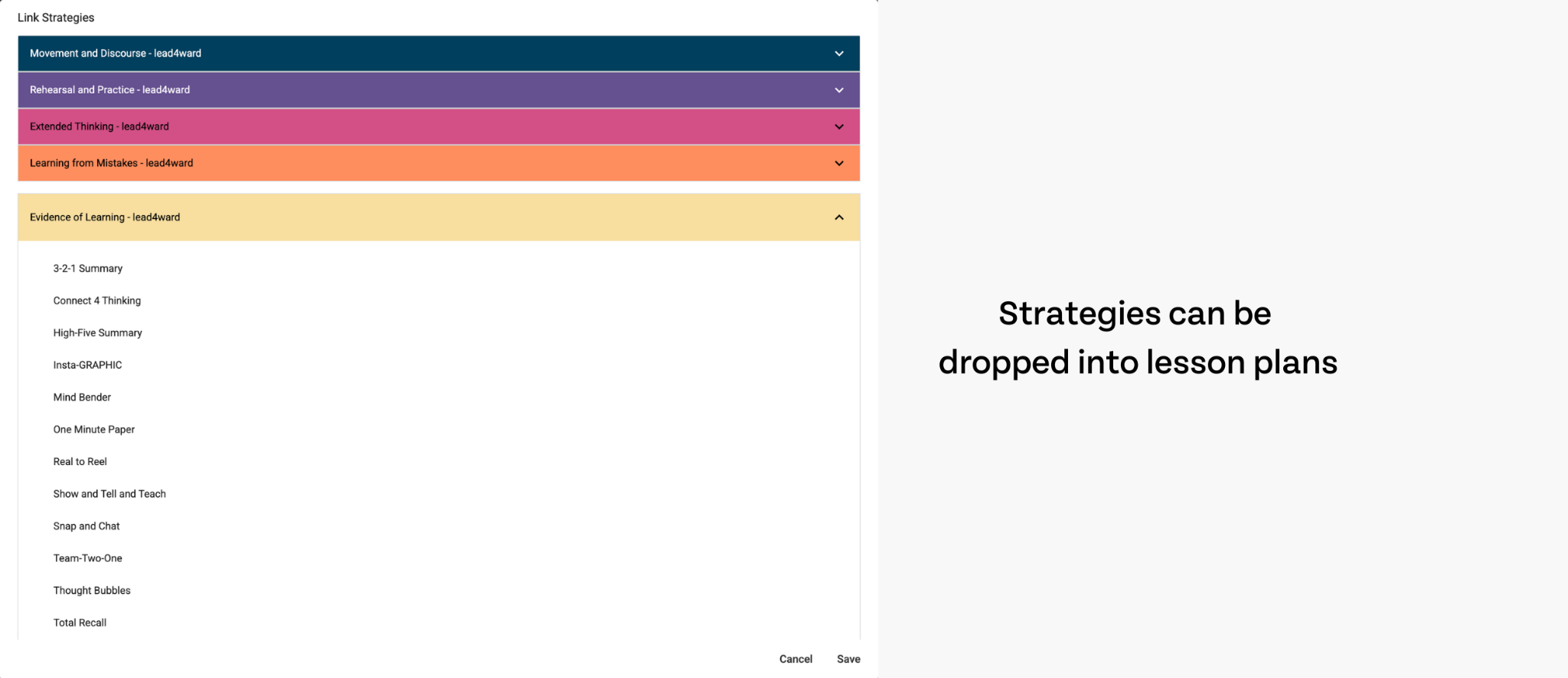

Scaffolding often takes the form of common strategies, such as collaborative learning. Administrators can add teaching strategies to Beacon that teachers can easily drag and drop into their planners.

So, for example, if you know that the majority of your students are in the early stages of learning and will likely need their practice task modeled for them, the teacher can drag the “modeling” strategy into the planner. According to their pre-test data, however, several students already possess a basic understanding of the concepts. So, maybe she’ll incorporate “group work” and “co-teach” strategies into the lesson as well, allowing these more advanced students to practice some enrichment while she attends to the rest of the class.

Planning, in general, is easier with Beacon. Because everything lives within the software, you don’t have to hunt down your resources, your strategies, or your lesson plans to get class going. Everything is in one place.

When scaffolding, it’s important to see not only all of the resources that are available to you, but also all of the resources you could use if the lesson isn’t as effective as you hoped it would be. Let’s say you teach a lesson that leaves students more confused than ready for their homework. You’ve got 15 minutes left to steer them back on course.

Simply head to your planner and search your resource library for another example, another activity, or a strategy that can help you teach your lesson. You could also check your planning blocks to see if you have any multimedia resources that may help the lesson sink in another way.

Pivoting is easier with Beacon because you don’t have to search your 7-layered Google Drive folder system with weird permissions to find the resources you need. It’s also easy to move lessons from day to day and adjust your plans based on how your students are grasping the concepts they need to move on.

No software? No problem.

If you don’t have software (and likely can’t just send those kinds of requests up the chain), that doesn’t mean you’re stuck using gut instinct and the last crumbs of your resolve to reach students.

While we don’t want this resource to drag on forever, here are some additional resources that can help you integrate these student-centered practices into your teaching, software or no software:

Easy differentiation tips for teachers

How to Implement MTSS into your classroom

We’re serious about those “aha” moments

You don’t have to be an Eduphoria customer to get tips, advice, and insights. If you’re not already following us on social media, hit the buttons at the bottom of the screen. If you want to stay up-to-date on our publications and learn more about how our software really works in the classroom, subscribe to our newsletter. We publish a monthly “updates” newsletter, where you can stay up-to-date with all things Eduphoria, and we publish a “Spotlights” newsletter, packed with useful tips for educators and Eduphoria software users. We can’t wait to see you there.

.png)

.png)